The story of Williams isn’t just about beautiful gardens or well-planned parks. It’s about how one designer’s vision evolved over decades, shaping how we think about the relationship between people and nature. What started as simple rural landscapes transformed into complex urban planning concepts that still influence designers today.

When you walk through a modern park or admire a carefully planned garden, you’re probably experiencing the legacy of someone named Williams. Not just any Williams, but the family whose approach to landscape design has become a cornerstone of contemporary outdoor architecture. This isn’t just about pretty pictures or fancy plants. This is about understanding how one family’s philosophy changed how we see our relationship with the natural world around us. Think about it – every time you sit in a public space designed with thoughtful consideration for both beauty and function, there’s a Williams influence somewhere in that design. The evolution wasn’t sudden. It happened slowly, like a river carving through stone over many years.

Early Foundations: Rural Beginnings

Williams’ early work began in the countryside, where they learned fundamental lessons about how nature works. These weren’t just pretty places to look at – they were functional spaces that worked with the land rather than against it. Picture a small farm in the 1960s, with Williams working alongside local farmers to create spaces that served both practical needs and aesthetic desires. The philosophy was simple but powerful: let the land speak first, then add your touch. This approach meant using native plants, respecting existing topography, and creating spaces that felt like they belonged naturally in their environment. Early projects showed a deep respect for the soil, water flow, and local wildlife habitats. These weren’t flashy designs. They were quiet, thoughtful interventions that made the most of what was already there. The foundation was built on observation, patience, and understanding that good design starts with listening.

Transition Period: Bridging Nature and Urban Life

As cities grew, Williams faced a new challenge. How do you bring those same principles of natural harmony into crowded urban environments? This period marked a major shift in thinking. Instead of just working with untouched landscapes, they had to learn how to create breathing room within concrete jungles. Imagine trying to plant trees in tight city lots while considering underground utilities, foot traffic, and weather conditions. The approach became more sophisticated. They began incorporating elements like green walls, pocket parks, and vertical gardens. These weren’t just decorative features – they were solutions to urban problems. The philosophy shifted slightly, moving from ‘working with nature’ to ‘creating harmony between nature and human needs.’ Streetscapes started featuring more trees, benches, and open areas that encouraged people to slow down and connect with their surroundings. The focus was on making urban life more livable, not just prettier. This transition period was messy and experimental, filled with lessons learned from failed projects and breakthrough moments that changed everything.

Innovation Through Technology Integration

The digital age brought new tools and new ways of thinking about landscape design. Williams embraced technology early, not as a replacement for traditional methods, but as an enhancement. They started using computer modeling to predict how plants would grow, how water would flow, and how people would move through spaces. This wasn’t about losing the human touch – it was about making that touch more precise and effective. Smart irrigation systems meant less water waste and better plant health. GPS mapping helped them understand exactly how people moved through spaces, allowing for better placement of seating areas and pathways. Sensors in the ground could tell them when soil needed water or nutrients. The technology didn’t change the core philosophy – it helped refine it. Projects that once took months to plan now could be tested and adjusted quickly. This integration created a new standard for what landscape design could achieve. The balance between old wisdom and new tools became a defining characteristic of their later work.

Sustainability as Core Principle

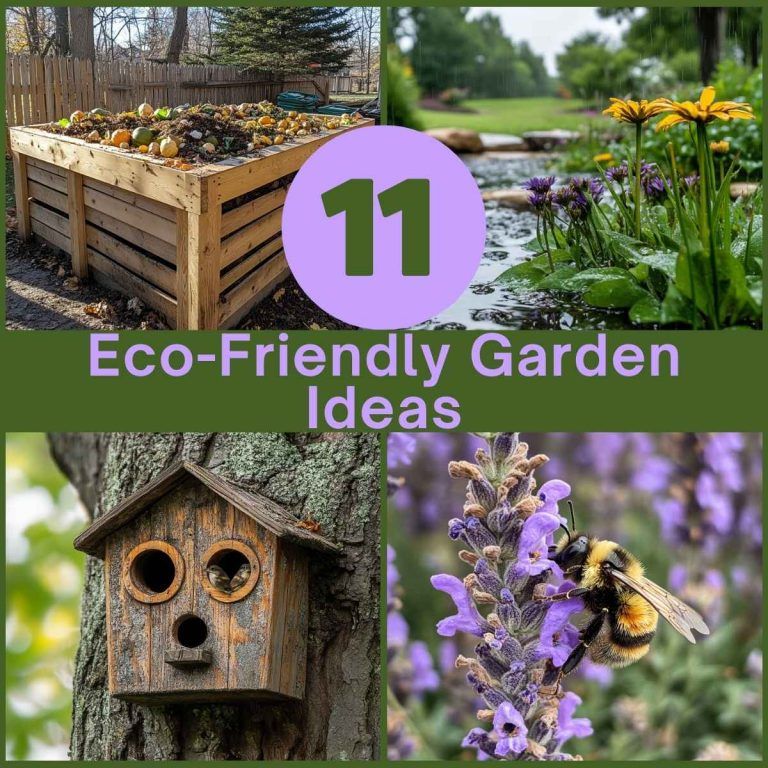

Sustainability didn’t become important to Williams overnight. It developed gradually as they observed environmental changes and realized their responsibility to future generations. What started as a concern for water conservation became a broader commitment to environmental stewardship. Their projects began incorporating rain gardens that filtered stormwater naturally, solar-powered lighting systems, and materials that wouldn’t harm local ecosystems. The concept of "designing with intention" expanded to include "designing with responsibility." They started teaching others about sustainable practices, showing how small changes in design could lead to significant environmental benefits. One project involved creating a school garden that provided food for the community while teaching children about growing their own vegetables. The garden became a model for similar projects across the region. Sustainability became more than just a buzzword – it was woven into every decision, every material choice, and every design element. The philosophy evolved from simply creating beautiful spaces to creating spaces that could heal and nurture the environment.

Community-Centered Design Approach

One of the most significant shifts in Williams’ philosophy came when they realized that good design isn’t just about aesthetics or functionality – it’s about people. They began involving communities directly in the planning process, asking residents what they wanted and needed. This wasn’t just about making people happy – it was about understanding how different groups used spaces differently. A playground designed for families might need different features than one designed for seniors. Community input led to innovative solutions like multi-generational gathering spaces and flexible areas that could serve multiple purposes. The approach was collaborative rather than directive. They learned that the best spaces were those where people felt ownership and pride. Projects often took longer because of extensive community involvement, but the results were worth it. People didn’t just use these spaces – they claimed them as their own. The philosophy evolved from designing for people to designing with people, creating a sense of belonging that went beyond physical beauty.

Modern Influence and Lasting Impact

Today, Williams’ influence can be seen everywhere from small neighborhood parks to large-scale urban developments. Their principles have been adopted by designers worldwide, though often adapted to local contexts. The way they approached sustainability has become industry standard, and their community-centered approach has inspired countless other designers. Modern landscape architects still reference their early work when facing challenges like limited space or environmental constraints. Their philosophy continues to evolve, but the core values remain constant: respect for nature, attention to human needs, and commitment to creating spaces that improve quality of life. The legacy isn’t just in completed projects, but in how they taught others to think about landscape design. Many current design schools teach Williams’ methods as foundational knowledge. The influence extends beyond design itself, touching urban planning, environmental policy, and community development. Their work reminds us that good design is ultimately about improving human experience, not just making things look pretty.

The evolution of Williams’ landscape design philosophy shows us that great design isn’t about following trends or using the latest technology. It’s about understanding the fundamental relationship between people and their environment. From rural farms to bustling cities, from traditional methods to cutting-edge technology, their approach has remained consistent: create spaces that work for everyone. Every time you enjoy a well-designed park or appreciate a thoughtfully planned garden, remember that you’re experiencing the result of decades of careful thinking and experimentation. Williams didn’t just design landscapes – they designed better ways for people to live together with nature. Their legacy lives on in every space where people feel comfortable, connected, and inspired to spend time outdoors. The question isn’t whether Williams influenced your local park or garden – it’s how much that influence shaped your daily experience of the outdoors. Their work continues to remind us that thoughtful design can transform ordinary spaces into extraordinary experiences.