Washington DC isn’t just the nation’s capital—it’s also a living museum of American landscape architecture. What started as grand visions for monumental parks has evolved into a complex web of modern urban design that influences cities nationwide. Every tree-lined boulevard, every pocket park, and every public space tells a story of ambition, politics, and the changing relationship between people and nature.

When you walk through Washington DC today, you’re stepping through centuries of planning decisions, political maneuvering, and artistic vision. The city’s landscape isn’t accidental—it’s the result of deliberate choices made by architects, planners, and citizens over more than two hundred years. From the original grid system designed by Pierre Charles L’Enfant to today’s smart growth initiatives, DC’s outdoor spaces reflect both the ideals of its founders and the realities of modern urban life. Think about it: when you see those perfectly aligned avenues or the way trees frame government buildings, you’re witnessing the culmination of decades of landscape evolution.

The Birth of a Capital’s Green Vision

Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s original plan for Washington DC was revolutionary for its time. His vision went beyond simple street layouts—he imagined a city where nature and civic purpose intertwined. The master plan included broad boulevards, large open spaces, and strategic placement of trees and gardens. This wasn’t just about making the city look pretty; it was about creating a democratic environment where citizens could gather, reflect, and participate in civic life. L’Enfant’s approach influenced urban planners worldwide, establishing DC as a pioneer in integrating green infrastructure into capital city design.

The early 1800s saw the first implementation of these ideas. The President’s Park, created in 1800, became the first major public green space in the city. It wasn’t just a park—it was a statement about what America could be. The careful positioning of trees and the symmetrical layout showed that even in a young democracy, there was room for beauty and order. These early efforts established the precedent that public spaces should serve not just as recreational areas, but as symbols of national identity and democratic values.

Victorian Era Expansion and Social Reform

As Washington DC grew through the mid-1800s, landscape architects began to think about parks not just as decorative elements but as social tools. The Victorian era brought a new understanding of how green spaces could improve public health and social conditions. During this time, the city expanded its park system significantly, adding places like Rock Creek Park and the National Mall.

This period also saw the influence of the Garden Movement, which emphasized the importance of nature in urban environments. Landscape architects began incorporating more diverse plantings and designing spaces that encouraged community gathering. The idea that parks could serve as democratic spaces where people from all walks of life could meet became central to the city’s planning philosophy. Many of these early designs still exist today, showing how thoughtful planning can create lasting public benefits.

One particularly interesting example is the creation of the National Park Service in 1916, which fundamentally changed how DC approached landscape preservation. The service brought together federal resources and local planning to ensure that important green spaces weren’t lost to development. This partnership between federal agencies and local communities became a model for other cities.

The Rise of Professional Planning

The early 1900s marked a turning point in DC’s approach to landscape architecture. As the city matured, planners began to take their work more seriously. The emergence of professional landscape architecture as a field meant that designers had more training and authority in shaping the city’s appearance. This shift led to more sophisticated approaches to urban design and environmental planning.

The Olmsted Brothers firm, famous for designing Central Park in New York City, also worked on several projects in DC. Their approach emphasized naturalistic design and the integration of parks with the surrounding urban fabric. They believed that good landscape design should feel organic rather than artificial, creating spaces that people could inhabit naturally. This philosophy influenced how later planners thought about creating welcoming, functional public spaces.

During this period, DC also began to grapple with the challenges of rapid urbanization. As more people moved to the city, planners had to think about how to provide adequate green space while managing density. The result was a more systematic approach to park planning that considered population distribution, accessibility, and environmental needs. This planning approach helped establish DC as a leader in urban green space management.

Post-War Urban Renewal and Modern Challenges

After World War II, Washington DC faced many of the same challenges that other American cities experienced during the suburban boom. The middle class moved to the suburbs, leaving urban cores struggling with decay and underinvestment. This period brought new pressures on the city’s landscape architecture. Planners had to balance maintaining historic green spaces with addressing the needs of a changing urban population.

The urban renewal movement of the 1950s and 60s brought both opportunities and problems. Some projects successfully revitalized neighborhoods, while others destroyed existing communities and green spaces. The construction of highways and large buildings often disrupted the carefully planned relationships between parks and urban areas that had been established in earlier decades. However, this period also saw important innovations in how cities could integrate green infrastructure with modern urban development.

One significant change was the growing awareness of environmental issues. By the 1970s, planners began to consider how landscape architecture could address pollution, stormwater management, and climate resilience. The concept of sustainable urban design started to take root, influencing how future projects would be planned and executed. This shift represented a fundamental change in how DC viewed its relationship with the natural environment.

Contemporary Innovation and Community Engagement

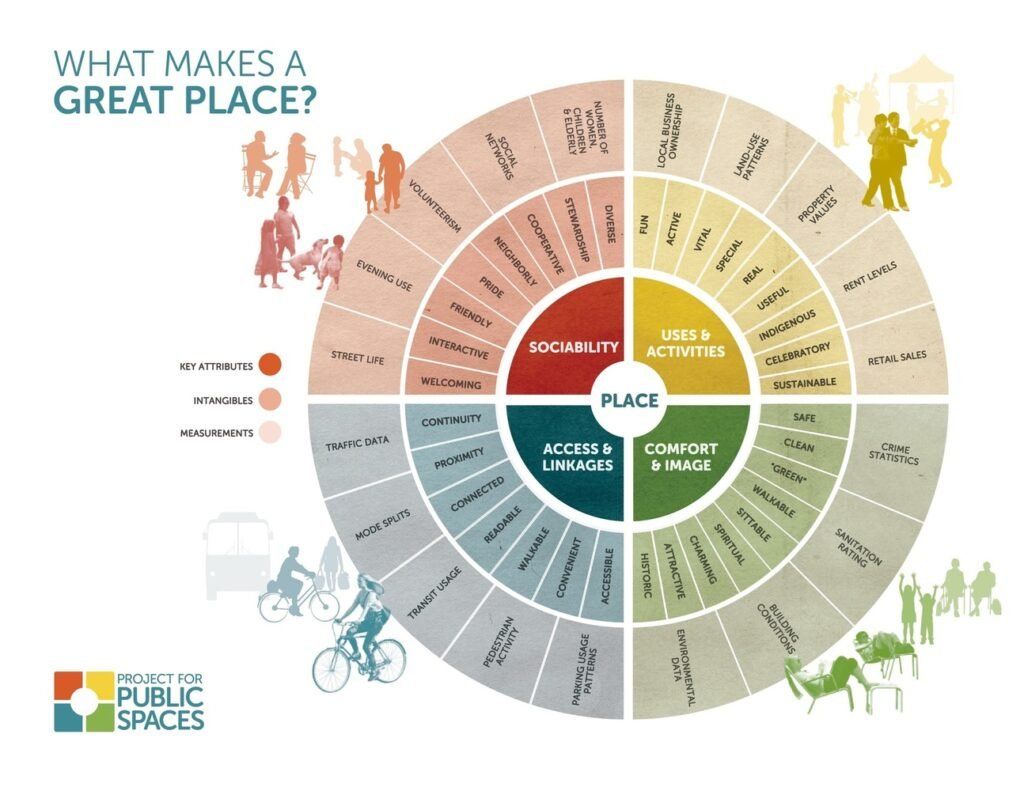

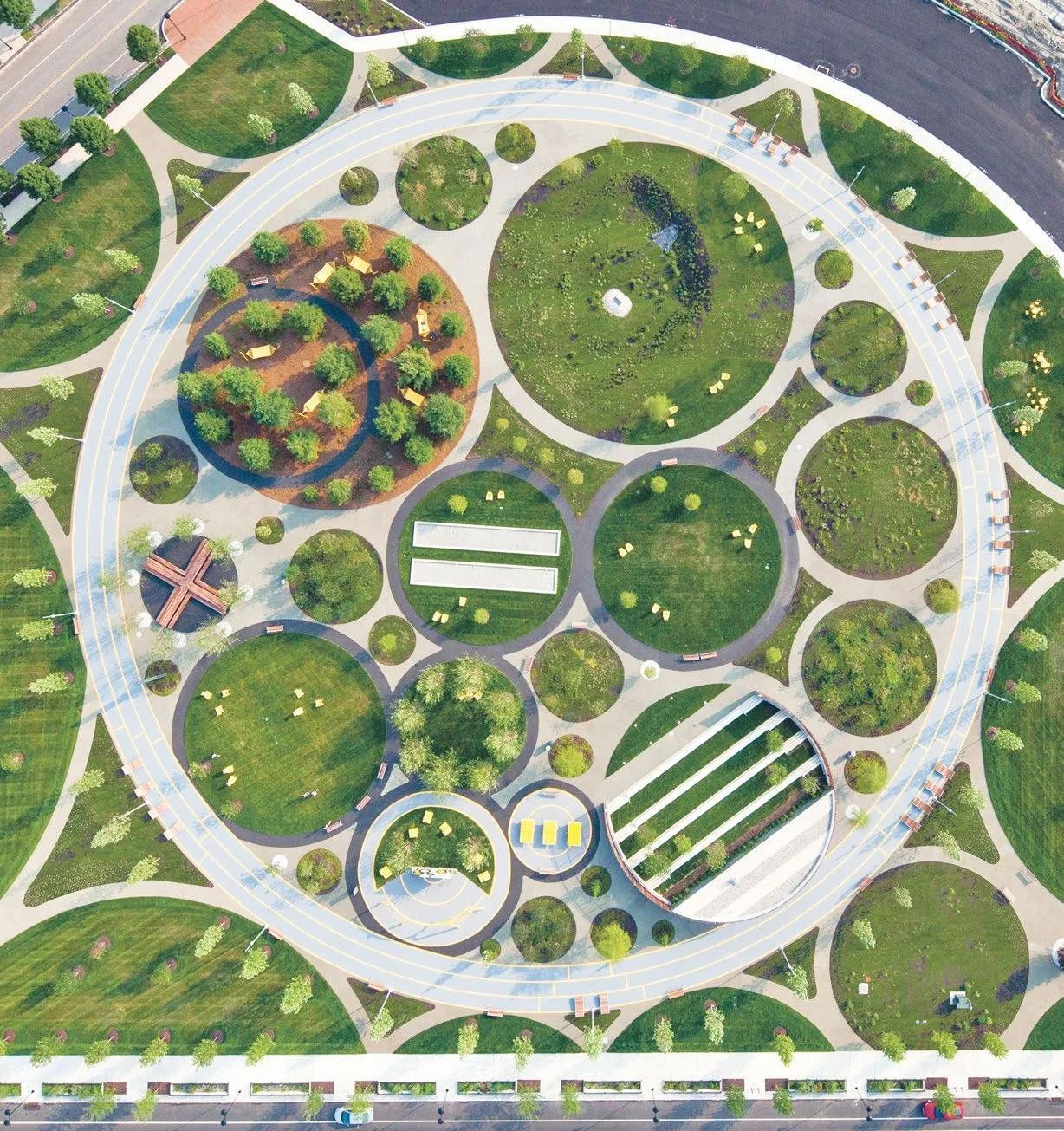

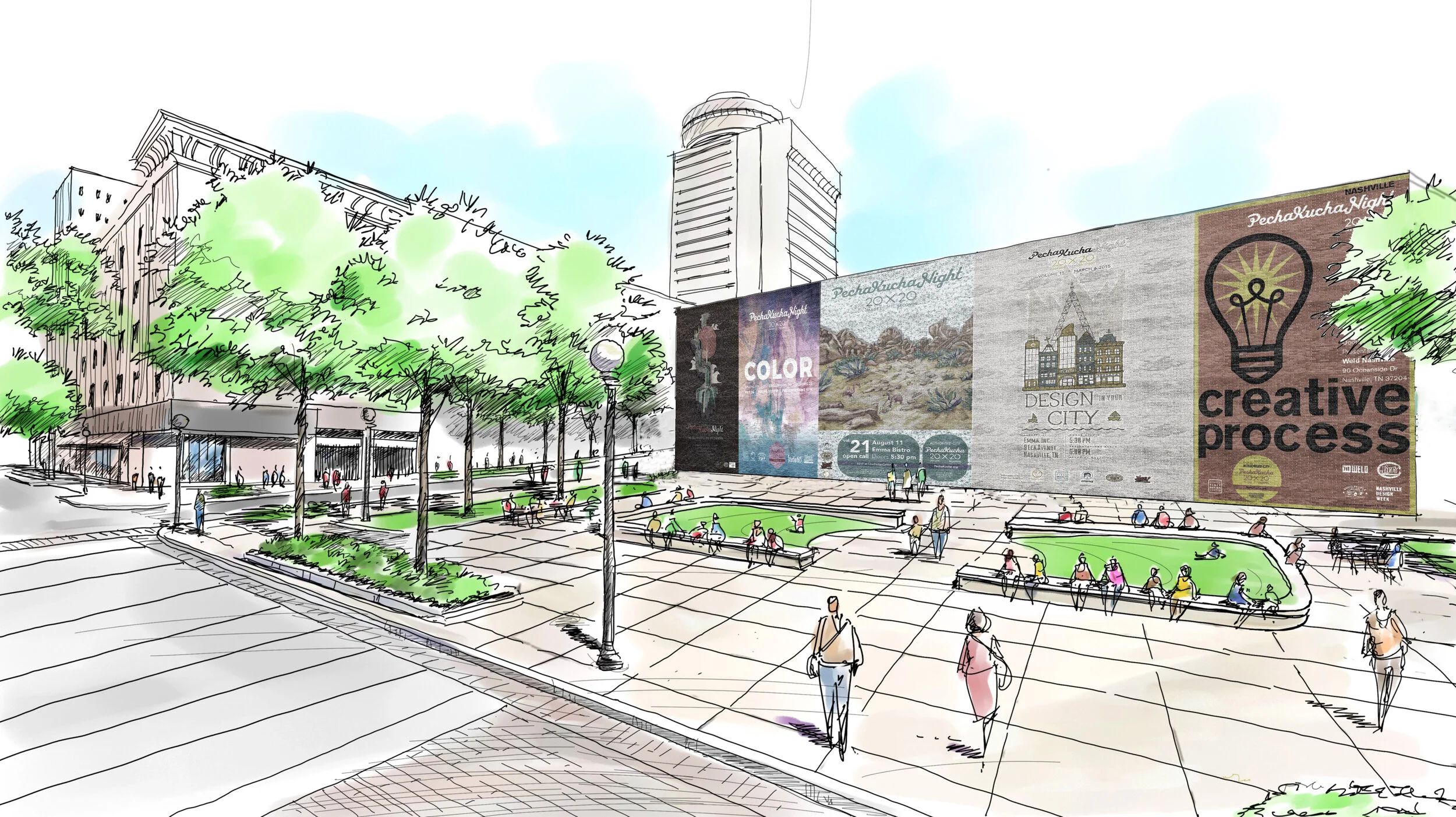

Today’s Washington DC landscape architecture represents a blend of historical respect and cutting-edge innovation. Modern planners work with communities to understand how people actually use public spaces, rather than assuming what they might want. This participatory approach has led to more inclusive and effective design solutions.

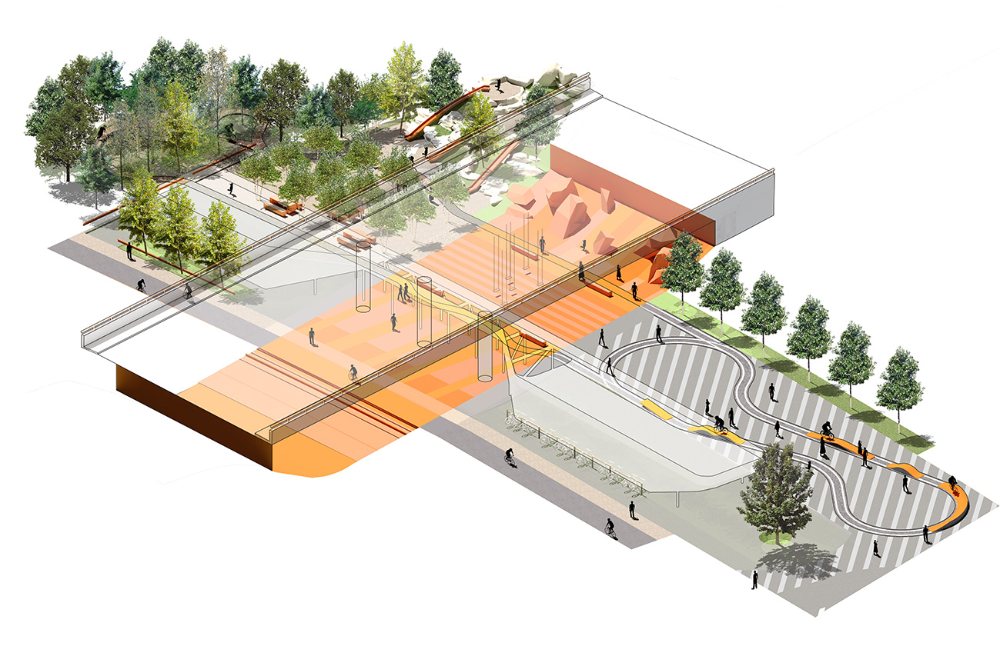

Technology plays a bigger role than ever before. Digital tools help planners visualize how changes will affect sunlight, wind patterns, and pedestrian flow. Smart irrigation systems and sustainable materials make maintenance more efficient. But perhaps most importantly, there’s a renewed focus on equity—ensuring that all residents have access to quality green spaces regardless of neighborhood or income level.

Recent projects like the Anacostia River restoration demonstrate how landscape architecture can tackle complex environmental challenges while creating beautiful public spaces. The project involved removing decades of pollution and restoring natural habitat while providing new recreational opportunities for local residents. It shows how modern landscape architecture can serve multiple purposes simultaneously: environmental restoration, community engagement, and aesthetic improvement.

The city has also embraced the concept of "green infrastructure"—using natural systems to manage water, air quality, and temperature. Rooftop gardens, bioswales, and permeable pavements are becoming common features in new developments. These innovations show how DC continues to evolve its approach to urban design while honoring its historical foundations.

Looking Forward: Sustainability and Inclusive Design

Current trends in DC landscape architecture point toward a future that balances preservation with innovation. Climate change considerations now shape every major project, from the design of new parks to the renovation of existing ones. Planners are selecting plants that can withstand changing weather patterns and designing spaces that can handle extreme temperatures and precipitation events.

There’s also growing emphasis on making public spaces more accessible and welcoming to everyone. This includes physical accessibility for people with disabilities, but also cultural accessibility that respects the diversity of DC’s population. Designers are working closely with community groups to ensure that new projects reflect the needs and values of local residents.

The future of DC’s landscape architecture also involves thinking about how technology and nature can work together. Smart sensors can monitor soil moisture and air quality, helping maintain healthy ecosystems while reducing maintenance costs. Virtual reality tools allow planners to test different design scenarios before building anything.

Perhaps most exciting is the potential for DC to become a model for other cities facing similar challenges. Its experience with balancing historical preservation, environmental sustainability, and community needs offers lessons for urban planners everywhere. The city’s commitment to public participation and evidence-based design makes it a valuable case study for anyone interested in creating better urban environments.

Washington DC’s journey from a visionary city plan to a modern urban landscape reflects the broader evolution of American cities themselves. The lessons learned here—from L’Enfant’s grand vision to today’s sustainable design practices—offer valuable insights for communities seeking to balance growth with environmental stewardship. Every time someone sits on a bench in a DC park or walks through a newly designed street, they’re participating in this ongoing story of urban transformation. The city’s landscape architecture isn’t static; it continues to evolve, shaped by new technologies, changing demographics, and evolving understandings of what makes a place truly livable. What’s next for DC’s outdoor spaces? That remains an open question, but one thing is certain—the city’s green legacy will continue to influence how we think about public spaces for generations to come.